Shelter and shadeKathmandu, NepalI finally found an umbrella man, on my way to CIWEC clinic. He sits by

the roadside under a tiny blue-tarp lean-to. He's little more than a child, and speaks almost no English. But his slender, tiny fingers work

delicate miracles on broken parasols.

I was always taught that umbrellas were disposable. If an umbrella breaks in America, you just buy a new one. There is no one who would even think of repairing it, much less know how to do so.

Here, just about anything can be and is repaired - people simply can't afford to toss things aside. The cobbler will even

painstakingly sew plastic flip-flops back together.

I'm a bit attached to my green folding umbrella. It's nothing special, but I bought it in Kandy, Sri Lanka in March last year, where the

alternating rain showers and blazing sun make it an absolute necessity. In Sri Lanka, there are entire umbrella stores (In Tamil an umbrella is called "kooday"). This umbrella has been with me ever since, through three countries. I hate to give up on it, even though now it has a broken metal rib and a couple of holes in the vicinity. I love the fact that the inside tag is in curly Sinhalese script.

There are shoe repairmen (cobblers)

on every other urban corner, all belonging to one of the

"lowest" castes in Hindu society because they work with leather.

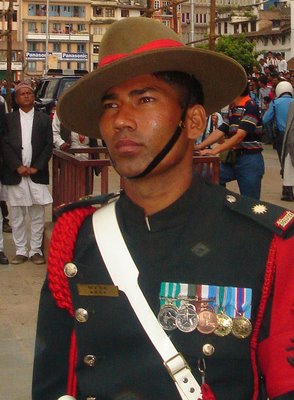

An umbrella man, while also "low" caste, is a bit more specialized. This one is a thin, dark brown boy with an enormous helmet of glossy black hair. His "Indian" features (round, not almond eyes; full lips, and dark brown skin) mark him as a Madhesi, or native of the Terai - the hot, flat, fertile plains near the IndoNepali border.

"Maithali bholnu hunchha?" (You speak Maithali?) I offered, hoping a familiar name - Maithali is a minority language spoken in Terai - would put him at ease. "Maithali nahi, Bhojpuri," he said softly, averting his eyes. I asked him "your native place?" and he answered with the name of his village, which escaped his lips

like a whisper. Something sinuous, like Siraha, Sarahi, or Senauli.

I squatted next to him, watching as he opened his homemade repair kit, a metal can that looked like a Danish cookie tin. All shapes and sizes of metal bits, most of which were scrap;

a motley assortment of thread colours, needles of various sizes, scissors, and a tiny pair of rusty pliers were inside.

The boy's father - a paunchy, balding carbon copy whom I instantly disliked, probably because he stood idle while his young boy did all the work - came along and insisted that I sit on the "good" chair. In this case, the good chair was a stool woven of cane covered in colourful plastic threads.

"It is the custom," as they say here, to offer a guest the chair - usually, there's only one chair in the place.

Often my hosts embarrass me by taking the chair away from the elder in the room, and insisting I sit there instead.

I see this multi-coloured stool all over Nepal, but never in India, where it's all machine-made moulded plastic furniture these days. Every bus here has a couple of these stools - they plop them down in the aisle to make more seating.

The boy carefully selected the closest matching thread in his repertoire, a dark blue colour. His

tiny fingers threaded the needle, then worked the blue thread through the tiny eyes of the umbrella's metal underpinnings. His father stood over him sternly, and I got the feeling that if the boy made a mistake, he might well get cuffed on his glossy black head.

It was 3.30 p.m.

Immaculate, uniformed children were

parading home from school, toting bright-coloured book bags brimming with their futures. The contrast was almost physically painful to watch - surely the Umbrella Man (boy?) had never gone to school.

His repair of the

broken metal rib was really amazing. He fished, from among his assorted metal scraps, a piece of aluminum just the right width. This he measured, and cut down to size with the rusty pliers. His motions were so intimate with the umbrella rib, I almost felt I had to look away. He bent low over the umbrella, pinching and pressing the metal rib into place.

A fair-skinned local lady came by and interrupted the operation. She complained in Nepali about the scuffed heel on her shoe - a frivolous

white plastic sandal with a stack heel. After a bit of theatrical teeth-sucking and a eyeball-rolling disapproval, she paid him 20 rupees for his work. She retired into the building behind their blue-tarp lean-to.

The boy then resumed stitching up the quarter-sized hole in my umbrella, almost good as new. In less than ten minutes, my Sri Lanka Kooday was miraculously whole again. I opened and shut it a few times, just to make sure.

"How much you give?" blustered the father.

The correct price was probably 30 rupees or less. All I had in my bag was a fifty.

"Fifty rupees," I said.

"Fifteen??!" the father spluttered. Fifteen and Fifty are commonly mistaken for one another here.

"No,

fifty. Pachas rupiyah," I said gently. I have always been an advocate of paying the correct local price, but I just couldn't bargain with these people living on the side of the road. The father smiled with approval. He had gotten an extra twenty rupees from the

gori touriss.It was

starting to rain as I snapped the boy's photo. I had to stand close under the tarp, so the camera wouldn't get even a drop of rain. Even a tiny bit of rain is ruinous for digital equipment. He was so engrossed in his work, I don't think he noticed my camera.

down (obscure, community-based, secretive besides the language problems) and documenting them. Last night I went to Lalitpur (Patan) to see the Ashtamatrika (Eight Goddesses) dance of the Newari Buddhist community. I only have time to upload one photo right now (before running to Immigration).

down (obscure, community-based, secretive besides the language problems) and documenting them. Last night I went to Lalitpur (Patan) to see the Ashtamatrika (Eight Goddesses) dance of the Newari Buddhist community. I only have time to upload one photo right now (before running to Immigration).

days I couldn't log into Blogger

days I couldn't log into Blogger