Refugee NationKathmandu, Nepal

Everyone knows about the Tibetan refugees; they are very high-profile and have a dramatic, romantic story. Tibetans are still coming over the mountains - still escaping Chinese occupied Tibet. But probably 20% of the city of Kathmandu - maybe more - are some kind of refugee.

are still coming over the mountains - still escaping Chinese occupied Tibet. But probably 20% of the city of Kathmandu - maybe more - are some kind of refugee.

Besides the Tibetans, there are several Bhutanese Refugee camps here in town. Meant to be temporary, like all such camps, the Bhutanese have been there nearly 16 years. King Wangchuk, an absolute if otherwise somewhat enlightened monarch in the neighboring mountain kingdom, kicked out lots of ethnic Nepalis who had been born and raised there (they were demanding things like "rights") in the early 1990s. The UN Human Rights Commission is here investigating the Bhutanese refugee camps this week; yesterday a bunch of protesting Bhutanis were arrested in front of the SAARC Secretariat.

Then there are Biharis - refugees from comparatively prosperous neighbor India. Ordinarily Nepalis go south to find work in India. There are some 1 million Nepalis working there now, largely as waiters or hotel staff; the stereotypical Nepali diaspora job is that of security guard ("bahadurs" - a Nepali word meaning courageous). These reverse Indian migrants are fleeing the state of Bihar, notorious for its poverty, violence and corruption. With their distinctive Indian features - prominent noses, enormous bushy moustaches, large, liquid eyes and unsmiling faces giving them a somewhat doleful look - they are easily spotted selling fruit from large bicycle baskets all over town. Every time I buy fruit, I ask them "what is your native place?" So far, they have all answered "Bihar." They are thrilled that I even know one or two cities in their state and that I have ridden through it, however briefly, on the train.

corruption. With their distinctive Indian features - prominent noses, enormous bushy moustaches, large, liquid eyes and unsmiling faces giving them a somewhat doleful look - they are easily spotted selling fruit from large bicycle baskets all over town. Every time I buy fruit, I ask them "what is your native place?" So far, they have all answered "Bihar." They are thrilled that I even know one or two cities in their state and that I have ridden through it, however briefly, on the train.

Yet another category of Indian refugee comes from Kashmir. Theirs is a diaspora of long standing. The Kashmiri conflict needs little introduction; because of it, green-eyed, fair-skinned Kashmiri men (known as much for their butter-tongued salesmanship as for their good looks) can be found in curio shops from Ladakh to Kerala. I would imagine the Kashimiri diaspora accounts for a good percentage of Nepal's very small Muslim minority. Where are the Kashmiri or Bihari women who must have accompanied their men? Do they stay at home in purdah ( Muslim seclusion of women), or tending children? or did they stay behind, leaving the men to dream of a day when they could earn enough money to return home and marry? A few days ago, I saw two tall, thin women dressed in the unmistakeable style of far northern India. Punjabi suit with churidhar pants, chunri (long scarf) pulled over the hair, no bindi on the forehead - that means, she's Muslim. The younger one could have been my sister, her features were so Caucasian. They were so exotic in these surroundings, I sprinted to catch up to them. "Place you are coming from?" I asked breathlessly. The elder one couldn't understand. "Kashmir," said the younger girl; "you are from?" "America."

Muslim seclusion of women), or tending children? or did they stay behind, leaving the men to dream of a day when they could earn enough money to return home and marry? A few days ago, I saw two tall, thin women dressed in the unmistakeable style of far northern India. Punjabi suit with churidhar pants, chunri (long scarf) pulled over the hair, no bindi on the forehead - that means, she's Muslim. The younger one could have been my sister, her features were so Caucasian. They were so exotic in these surroundings, I sprinted to catch up to them. "Place you are coming from?" I asked breathlessly. The elder one couldn't understand. "Kashmir," said the younger girl; "you are from?" "America."

The ladies were carrying water in what looked like old-fashioned plastic gasoline jugs, the kind with a handle on one side. Since there is no running water near their tiny flat, she told me they go to fetch water from a public tap some four times a day. They trudged up the sidewalk with the plastic jugs perched on one shoulder, heads held high.

Internal Affairs

Then there are the Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) - those who

've been flooding Kathmandu escaping the Maoist/RNA conflict in their villages for the last few years. The Kathmandu population has mushroomed recently, mostly young men fearing recruitment or death at the hands of either army. Many young women have fled as well. Some find gainful employment; some are driven to dance in the many strip bars in the tourist district; some turn to either outright prostitution or a "softer" kind involving a relatively wealthy city man or "foreign gentleman" they have met during their migration.

Still more Nepalis are just fleeing poverty and lack of opportunity in their rural districts, armed conflict or no. Maya is here with her 2 daughters and sick husband. The husband has TB and is just sort of acknowledged to be terminal. There is treatment for TB, but they seem to have accepted that he is dying. The husband just lies in bed all day (all he can do) while Maya and her daughters do a sort of hybrid job in Thamel, alternately selling small pocketbooks (the kind tourists use as money pouches) and when that fails, begging. Maya buys the bags wholesale for about 30NRs each and sell them for whatever they can get. If the tourist looks rich, they start at 500NRs (about $8.00). However, they will part with the bag for as little as 50NRs. The same bags are for sale in every single shop in Nepal; often for much better prices, but Maya and girls are counting on pity and immediacy (being in your face on the street, that is). I wonder to myself whether she purposely doesn't wash her girls properly for this reason.

Maya came here from Pokhara, the centrally located lake town, seeking treatment for her husband. They seem to have forgotten about that now and just accepted that he's dying. While we were talking to her, Maya started crying and said "I just wish someone would take her" (the baby) "back to America."

And of course, there are the expats...not tourists, but lifers. Foreigners who came for a season and stayed. They're all running from something - many seem to be running from conventional ideas of prosperity and all its confining trappings, as our Nepali neighbors are hoping to run toward them. They ran to a place where the human touch still counts, everything is not yet mass produced, and you can still ride a bicycle to work without getting run down by SUVs.

Most foreigners are involved in one or more charities, projects or volunteer work; like Renate, the Dutch Nepali resident and owner of the posh restaurant 1905 Kantipath. Renate is deliriously busy not only running his business, but with myriad projects and homegrown, small-scale charities which emphasize training and education.

Unlike India, the locals here don't seem to consider you "stupid" for wanting to help. And a heartening number of projects seem to do long-term, sustainable good.

I met Rachael as she was taping up

hand-written posters to the notice board of the posh Kathmandu Guest House. Rachael is a very low-budget traveller here from New Zealand. "I hope you don't mind eating here," she said quietly as we ducked into a dark, smelly local lunch joint where flies buzzed around the food counter. It turned out to be too dirty even for her, and we ate elsewhere. Her guest house is 150 NRs a day (about $2.00 US) and only has hot water from 8-10 in the morning. Rachael is trying to raise money for "her" family in the Langtang region. She met them while trekking, spent time with them and got to know their situation intimately. Rachael wants to collect $100 US to repair their leaking roof (especially now that it is monsoon) and is in the city collecting it - 100 NRs (that's about $1.50) at a time. Her sunspotted skin, worn out sandals and frequently stitched and re-stitched pants showed that she spent no money on herself. If she can buy a sheet of corrugated tin, Rachael can take it up to Langtang, tied onto the roof of a bus. (Anything and everything can be tied onto the roof of a bus here - I've seen full-sized sofas transported this way. It was amazing to see the men get it up there; but then, this is a land where five-foot men carry full-sized fridges on their backs.) From there, she will have to hire local men to carry it up to the family house. She's also collecting money to build a wall that will protect the family's apple orchard seedlings from the local deer, goats and pigs.

With $150 US, the family can buy a water buffalo, which will enable them to start a small-scale dairy business providing yogurt and milk to their neighbors.

Everyone gets involved, everyone has a project. No one, it seems, "belongs" here. Therefore, we all do. It's strangely liberating, and creates an environment in which anyone can fit in. Politicized enough to be relevant, romantic enough to be picturesque, bohemian enough to be accepting, and very international - a slice of Manhattan's 1980s East Village transplanted to a rain soaked mountain kingdom - Whoops! kingdom-slash-modern democratic republic... in the monsoon clouds.

Song of the Serpent

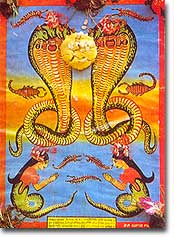

Song of the Serpent Naag Panchami is mostly celebrated by Hindus, but there is a Buddhist legend about the Nagas as well. When the Buddhist saint Manjushree stood atop Swayambhu hill that emerged from the water like a lighthouse, he struck his mighty sword and cleaved the lake in two, draining it and forming what's now the Valley. But he had to promise the Nagas we would always honour and worship them, because we took their land.

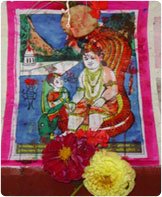

Naag Panchami is mostly celebrated by Hindus, but there is a Buddhist legend about the Nagas as well. When the Buddhist saint Manjushree stood atop Swayambhu hill that emerged from the water like a lighthouse, he struck his mighty sword and cleaved the lake in two, draining it and forming what's now the Valley. But he had to promise the Nagas we would always honour and worship them, because we took their land. special rice and red powder to the snakes. Then they tack up a fresh new snake-picture over every door. Gotta keep the earth spirits happy.

special rice and red powder to the snakes. Then they tack up a fresh new snake-picture over every door. Gotta keep the earth spirits happy.